Eating minimally processed foods and avoiding ultra processed foods (UPFs) could help people lose twice as much weight, a new trial has found. Sticking to meals cooked from scratch could also help curb food cravings, researchers suggest.

UPFs include the likes of processed meals, ice cream, crisps, some breakfast cereals, biscuits and fizzy drinks. They tend to have high levels of saturated fat, salt and sugar, as well as additives and ingredients that are not used when people cook from scratch, like preservatives, emulsifiers and artificial colours and flavours.

Trial splits participants into two groups

The trial, led by experts at University College London (UCL) and University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (UCLH), involved 55 people split into two groups. Half were given an eight-week diet plan comprising minimally processed foods, such as overnight oats and spaghetti bolognese, while the other half were given foods like breakfast oat bars or lasagne ready meals.

After completing one diet, the groups then switched. Researchers matched the two diets nutritionally on levels of fat, saturated fat, protein, carbohydrates, salt and fibre using the Eatwell Guide, which outlines recommendations on how to eat a healthy, balanced diet.

Processing impacts weight beyond nutrients

Dr Samuel Dicken, of the UCL Centre for Obesity Research and UCL department of behavioural science and health, said: "Previous research has linked ultra-processed foods with poor health outcomes. But not all ultra-processed foods are inherently unhealthy based on their nutritional profile." He said the main aim of the study was to explore the role of food processing and how it impacts weight, blood pressure, body composition and food cravings.

Some 50 people completed the trial, with both groups losing weight. However, those on the minimally processed diet lost more weight at 2.06 per cent compared to the UPF diet at 1.05 per cent loss.

Long-term projections show significant difference

The UPF diet also did not result in significant fat loss, researchers said. Dr Dicken said: "Though a 2% reduction may not seem very big, that is only over eight weeks and without people trying to actively reduce their intake."

"If we scaled these results up over the course of a year, we'd expect to see a 13% weight reduction in men and a 9% reduction in women on the minimally processed diet, but only a 4% weight reduction in men and 5% in women after the ultra-processed diet," Dr Dicken said. "Over time this would start to become a big difference."

Food cravings reduced with fresh meals

Those on the trial were also asked to complete questionnaires on food cravings before and after starting the diets. Those eating minimally processed foods had less cravings and were able to resist them better, the study suggests.

However, researchers also measured other markers like blood pressure, heart rate, liver function, glucose levels and cholesterol and found no significant negative impacts of the UPF diet. Professor Chris van Tulleken, of the UCL division of infection and immunity and UCLH, said: "The global food system at the moment drives diet-related poor health and obesity, particularly because of the wide availability of cheap, unhealthy food."

Calorie deficits differ between diet types

"This study highlights the importance of ultra-processing in driving health outcomes in addition to the role of nutrients like fat, salt and sugar," Professor van Tulleken said. The Eatwell Guide recommends the average woman should consume around 2,000 calories a day, while an average man should consume 2,500.

Both diet groups had a calorie deficit, meaning people were eating fewer calories than what they were burning, which helps with weight loss. However, the deficit was higher from minimally processed foods at around 230 calories a day, compared with 120 calories per day from UPFs.

UK population struggles with guidelines

Professor Rachel Batterham, senior author of the study from the UCL centre for obesity research, said: "Despite being widely promoted, less than 1% of the UK population follows all of the recommendations in the Eatwell Guide, and most people stick to fewer than half." The normal diets of the trial participants tended to be outside national nutritional guidelines and included an above average proportion of UPF, which may help to explain why switching to a trial diet consisting entirely of UPF, but that was nutritionally balanced, resulted in neutral or slightly favourable changes to some secondary health markers.

"The best advice to people would be to stick as closely to nutritional guidelines as they can by moderating overall energy intake, limiting intake of salt, sugar and saturated fat, and prioritising high-fibre foods such as fruits, vegetables, pulses and nuts," Professor Batterham said. "Choosing less processed options such as whole foods and cooking from scratch, rather than ultra-processed, packaged foods or ready meals, is likely to offer additional benefits in terms of body weight, body composition and overall health."

Expert backs realistic approach

Tracy Parker, nutrition lead at the British Heart Foundation, said: "These findings support what we have long suspected - that the way food is made might affect our health, not just the nutrients it contains. The way this study was designed means it is more reflective of real-world conditions than previous research on ultra-processed foods."

"Unlike earlier observational studies, this was a randomised controlled trial where participants were provided with all their meals, and the diets were carefully matched to meet the Eatwell Guide - this allowed researchers to isolate the effect of food processing itself, making it more likely that the differences seen after eight weeks were due to how the food in their diets was processed, not just what was in it," Parker said. "Completely cutting UPFs out of our diets isn't realistic for most of us, but including more minimally processed foods - like fresh or home cooked meals - alongside a balanced diet could offer added benefits too."

"Mediterranean-style diets, which include plenty of minimally or unprocessed foods such as fruit, vegetables, fish, nuts and seeds, beans, lentils and wholegrains, have consistently been shown to reduce our risk of heart attacks and strokes," Parker said.

(PA/London) Note: This article has been edited with the help of Artificial Intelligence.

3 godzin temu

3 godzin temu

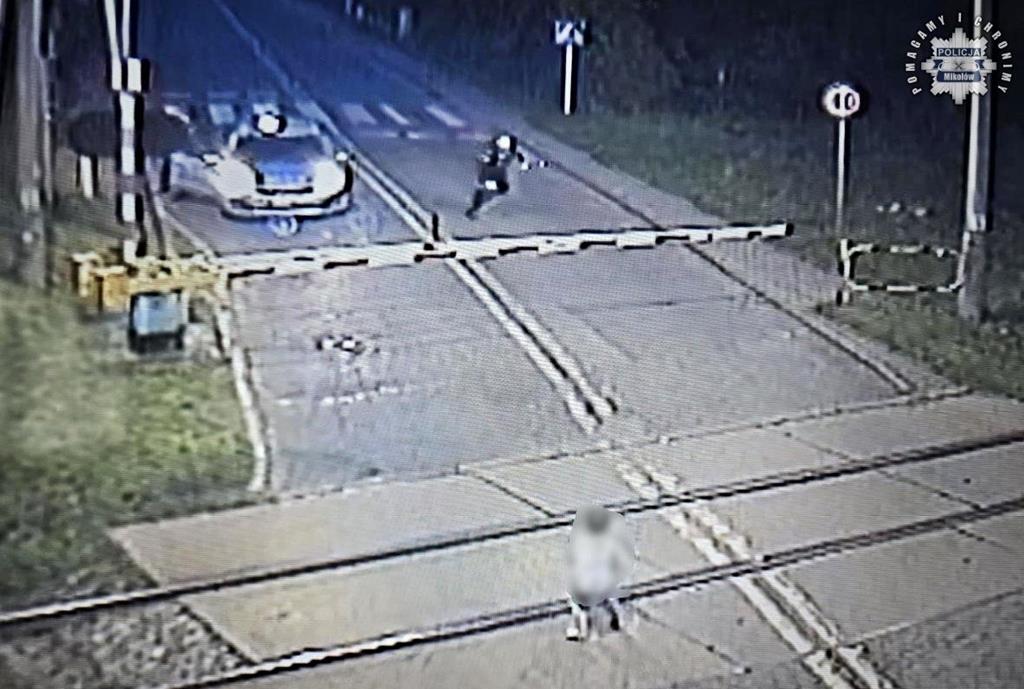

![[FILM] Mikołów: Chłopiec bawił się na torach, kiedy nadjeżdżał pociąg. Uratowali go policjanci](https://images5.polskie.ai/images/2217/32676734/d5e19d4eb9e259b52342b6f06eedd8d0.jpg)